This article is more than 1 year old

Who in America is standing up to privacy-bothering facial-recognition tech? Maine is right now leading the pack

'This technology is too dangerous to be regulated, it shouldn’t be used at all'

Feature The State of Maine has enacted what the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) describes as the strongest state facial-recognition law in the US amid growing concern over the unconstrained use of facial-recognition systems by the public and private sector.

The Maine bill, LD 1585 [PDF], forbids state officials from using facial-recognition technology, or entering into agreements with third parties to do so, except under a relatively limited set of circumstances having to do with serious crimes and searches of vehicle registration data. It imposes the sort of broad limitations that civil liberties advocacy groups have been advocating.

"Maine is showing the rest of the country what it looks like when we the people are in control of our civil rights and civil liberties, not tech companies that stand to profit from widespread government use of face surveillance technology,” said Michael Kebede, policy counsel at the ACLU of Maine, in a statement.

“The overwhelming support for this law shows Mainers agree that we can’t let technology or tech companies dictate the contours of our core constitutional rights."

LD 1585, we're told, was unanimously backed by the state's lawmakers, and became law without any need for approval by the governor.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report recommending that US federal agencies take steps to better understand and manage how they use facial-recognition technology. Twenty federal agencies currently use facial recognition, either their systems or third-party systems like Clearview AI or Amazon Rekognition. Fourteen rely on non-federal systems but 13 of these could not provide details about what their employees were using to the GAO.

And two week ago, a set of Democratic lawmakers reintroduced the Facial Recognition and Biometric Technology Moratorium Act, in response to reports about unregulated use of such systems.

- Detroit Police make second wrongful facial-recog arrest when another man is misidentified by software

- Detroit cops cuffed, threw a dad misidentified by facial recognition in jail. Now the ACLU's demanding action

- Mounties messed up by using Clearview AI, says Canadian Privacy Commissioner

- Amazon continues its ban on allowing police to use its facial-recognition software

But not all laws are so strict. The ACLU points to Washington Facial Recognition Bill (SB 6280), passed in 2020 with the support from Microsoft, as an example of weak legislation that fails to protect against mass surveillance.

Critics claim the technology is unreliable, discriminatory, and violates civil rights. For example, in January, 2020, Robert Julian-Borchak Williams was arrested by mistake in Michigan as a result of a flawed facial-recognition match.

Meanwhile, commerce steps in

Advocacy groups have also raised the alarm about the quiet use of facial-recognition technology in commercial applications. Fight for the Future, a digital rights advocacy group, points to the use of facial-recognition by payments system Stripe and hook-up hangout Tinder as examples of the trend.

Strip Identity, announced two weeks ago, provides a service that allows companies to identify customers by checking government IDs and selfies. "Stripe’s identity verification technology uses computer vision to create temporary biometric identifiers of your face from the selfies and the picture on your photo ID—and compares the two," the biz explains.

Stripe claims it does not see biometrics identifiers in its system and deletes those identifiers after 48 hours.

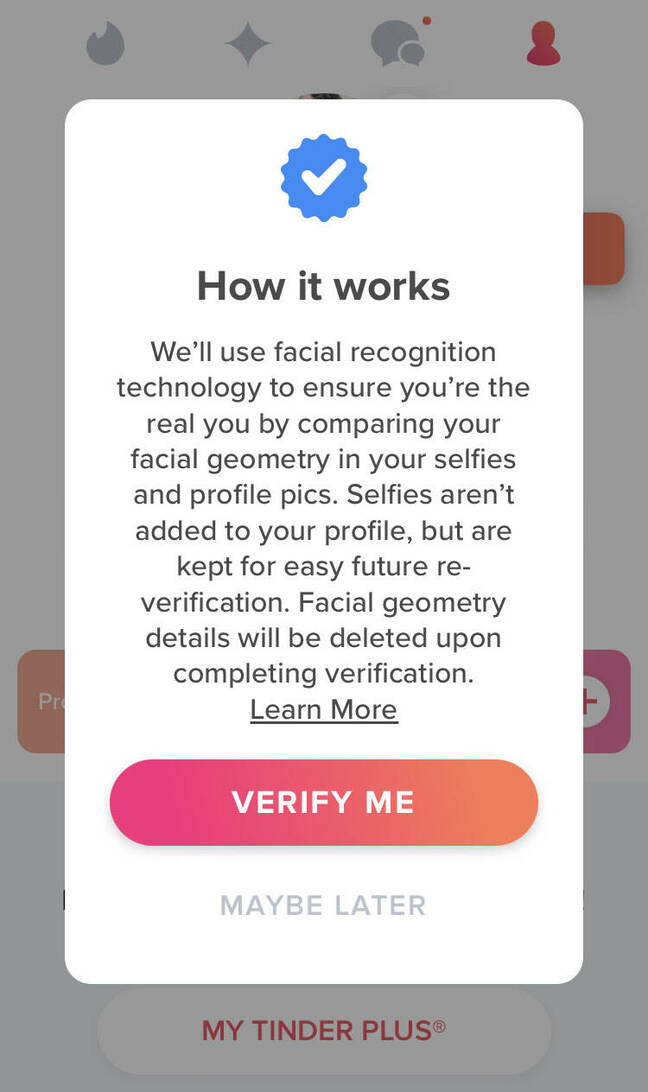

Tinder has also been using facial recognition for its Photo Verification service at least since June 2020. It recently added a popup in its app disclosing the use of facial-recognition technology.

The Register asked whether this was done for any particular reason. A Tinder spokesperson said, "Nope – we're just encouraging members to Photo Verify their profiles."

Caitlin Seeley George, Fight for the Future's director of campaigns and operations, told The Register via email that facial recognition should be banned entirely.

"We need a federal ban on facial recognition," she said. "This technology is too dangerous to be regulated, it shouldn’t be used at all."

The use of facial recognition by Stripe and Tinder, she said, is deeply concerning.

"These facial recognition systems will certainly result in discrimination: not only will there be cases where the technology is unable to correctly identify users, but companies could also use this tool to actively ban specific people from purchasing their products or using the apps," explained Seeley George.

"They also normalize the use of facial recognition in peoples’ lives, and further speed up its adoption across society in ways that abuse peoples' rights and put them in danger."

Asked whether there's any value to facial recognition, Seeley George said the technology does more harm than good.

"It doesn’t work, it builds databases of biometric data that can be targeted by those who want to do wrong, and it provides more opportunities for supercharged discrimination," she explained.

"When a company like Stripe makes facial recognition available to all users it makes the technology seem normal and okay for people to use, but this normalization is very problematic. People should not feel comfortable scanning their face anytime they want to buy something or access content online."

A mixed approach

Another online advocacy group, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, would prefer to see more measured limitations on facial-recognition technology on the basis that some uses can be positive.

"It does not follow that all private use of face recognition technology undermines human rights," the EFF said in a post earlier this year. "For example, many people use face recognition to lock their smartphones."

A complete ban on the technology, the EFF argues, would also disallow uses for research and activism.

Rachel Thomas, co-founder of fast.ai and the founding director of University of San Francisco Center for Applied Data Ethics, told The Register via email that she too favors targeted regulation.

"My view is that we would need to ban particular applications of facial recognition (e.g. ban its use in commercial or government settings) rather than banning the technology in the abstract," she said.

"I think that debates on whether you can prevent anyone in any context from doing facial recognition can be distracting, and that it's most useful to focus on practical applications and the people potentially being impacted."

Given the number of technology companies around the world that use facial recognition and the utility of the technology for law enforcement and commerce, it's difficult to believe those with a financial interest in face data would quietly accept laws prohibiting facial recognition.

"Companies are already trying to rebrand facial recognition because the term has become so toxic," said Seeley George.

"Microsoft recently started providing Australian police with 'object recognition' services, which you can imagine could be used in ways to try to identify or track specific people. Other companies are describing things as 'face scans' instead of 'facial recognition' to try to avoid scrutiny. So there’s no question that companies will try to avoid being targeted by this legislation."

Nonetheless, she argues nothing short of a total ban will do.

"Ultimately, facial recognition is dangerous no matter who is using it, and corporations and private entities with power are already using the technology in ways that put people in danger," she said.

"Much like how facial recognition supercharges racist policing, private entities can use facial recognition to discriminate against people and it can augment societal bias."

"So yes, we need to ban it all. That said, passing the federal facial recognition ban legislation would still be very real progress that will protect people being targeted by government and law enforcement use of the technology now." ®