This article is more than 1 year old

Dirty diesel backups will make Hinkley Point C look like a bargain

Capacity margin 0.1 per cent this winter – prepare to shiver

Britain signed off on the most costly energy deal it has ever made this week – but the price we agreed for energy from Hinckley is still lower than the peak prices that will hit British wallets even harder, and sooner.

Current commitments to renewable generation will cost each household £466 by 2020/21, the centre-right think tank the Centre for Policy Studies reckons. (Summary here)

Yet the CPS highlights something often overlooked – the volatility of the spot market. On September 14, the day-ahead electricity price hit £999/MwH for more than an hour. Typically the wholesale price hovers around £45/MWh.

This was the coincidence of unplanned shutdowns of our nuclear stations, the outage of the French interconnect, and a lovely heat wave. Hinkley Point C has a guaranteed price of £92.5/MWh, index-linked to 2012 prices. (National Audit Office nuke overview here, PDF)

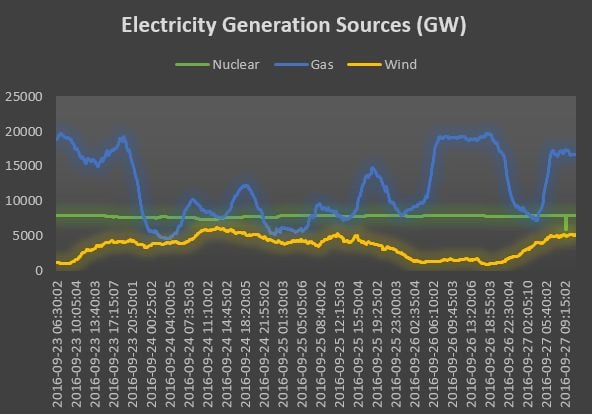

Gas and nuclear typically provide 70 per cent of our energy, with nuclear the most reliable and cost effective source for baseload. More of both sources would be the optimal cost effective energy strategy. But Britain’s dash for wind has hidden costs. Wind generates between close to zero and 11 per cent of electricity and the volatility has had a few side effects.

Wind makes the grid flakier, as Aussies found out this week. No sooner had the state of South Australia boasted about “going zero carbon” then it suffered black-outs.

When wind blows, energy is twice the price, but South Australia still needs to import it from other states when the wind doesn’t blow.

This week a storm was developing, and grid managers had lowered the voltage to cope with the surges caused by wind turbines. But wind operators, seeing the turbines crank up, opted to run them as long as they could rather than order an orderly shutdown. Then lightning hit the gas plant that acted as backup.

Another downside is less investment in gas. Barely over one tenth of the new gas capacity the British government said we needed in 2012 is being built, the CPS notes. The graph illustrates why: wind's intermittency makes gas much less efficient (and profitable) to run.

The £999/MwH may look like an eye-watering spot price, but we might have to get used to paying over the odds. Under pressure from special interests and EU directives, we’ve taken lots of useful energy capacity offline but just haven’t built enough power stations to replace them.

Comparison of UK gas, nuclear and wind generation over the past few days.

There's no lights on the Christmas tree, Mother...

This winter the capacity margin – the difference between capacity and demand – is predicted to be 0.1 per cent: that’s how much head room the UK has before emergency measures kick in. The foremost of these is the “Dad’s Army Diesel” or “Dirty Diesel” option of STOR, or the Short Term Operating Reserve.

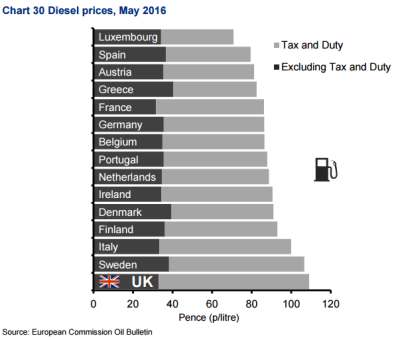

If we're relying on diesel to keep the lights on, it's a good job it's cheap. Er...

The UK pays more for diesel at the pump than anyone else in Europe, and the owners of STOR get paid for keeping the generators working but idle. According to trade association AMPS, the spot price for firing up STOR was between £90/Mwh and £350Mwh. But by definition, this is a seller’s market: the diesels only crank up when the UK is desperate. A winter in which the wind doesn’t blow should reveal how much these spike prices will be.

A study in 2012 by former World Bank economist Professor Gordon Hughes calculated that the UK could meet its CO2 reduction obligations for one tenth of the cost if it went for gas. He made very generous assumptions about the productivity of wind. In response, a Department for Energy and Climate Change spokeperson, indicating the extent to which the department was held captive by special interests, shrieked:

If this sort of short-sighted analysis informed our policies we’d not meet our carbon emission targets and keep the lights on, and the consumer would certainly be worse off.

The department has since been abolished but its policies survive.

For reference, the 2012 strategy from the now-abolished DECC is here, and up to date numbers on almost everything energy-related can be found in the Quarterly Energy Prices Report. (PDF)

The EPR reveals that poorest in the UK pay proportionally more for energy – around 10 per cent of their total expenditure, compared to three per cent for the wealthiest 10 per cent. This could explain why it’s the upper middle class who are keenest on expensive renewables: they can afford to be keen.

Virtue signalling is a luxury item. ®