This article is more than 1 year old

IPv6 growth is slowing and no one knows why. Let's see if El Reg can address what's going on

Get it? Address? As in, oh never mind

Analysis Stop us if you've heard this one before: the rollout of IPv6 is going slower than expected.

In fact, nearly seven years after the eternally optimistic World IPv6 Launch launched, we are still only at just over a quarter availability of the new internet protocol.

But if that wasn't bad enough, the latest news is that even that unimpressive level of growth is slowing and may even been tailing off.

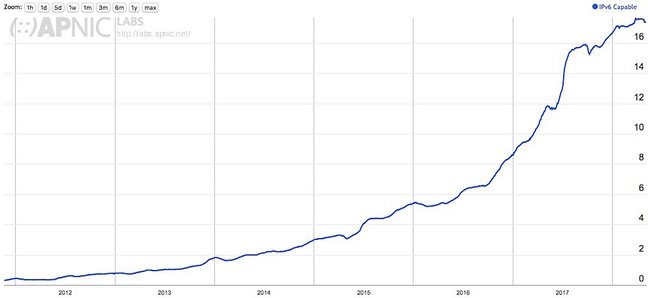

In the lead-up to regional internet registries literally running out of IPv4 blocks, it seems that quite a few big companies – including tech giants and ISPs – decided to go all-in on IPv6. And that led to a relatively fast growth in the availability of IPv6 – up from virtually nothing to around 15 per cent in mid-2017.

But as those address blocks really have run out, it appears as though the larger corporate world has moved IPv6 adoption in their minds from "important" to "nice to have." After all, their systems still work and users aren't complaining about not being able to get online (thanks increasingly to the work of engineers making the most out of what IPv4 they have).

As one avid IPv6 watcher – chief scientist of regional internet registry APNIC, Geoff Huston – has identified, the last four months of stats show a significant slowdown of IPv6 adoption.

The question is: why?

And Huston has done some analysis based on a number of different theories to see if he can figure it out - and, by extension, see what can be done to get IPv6 adoption moving again.

Driving seat

Here are some plausible theories:

- Rich countries and corporations are more likely to shift to IPv6 because they have the capital to do so and are looking ahead

- Companies undergoing rapid growth are more likely to go IPv6 because it's the future and they need to build out into a larger address space.

- Running out of IPv4 address will force companies – and countries – to shift to IPv6

- Competition will be an effective driver: if others in your market are going into IPv6, you need to keep pace with them for future competitiveness

Unfortunately, after pulling the stats and putting them into easily understandable graphs, Huston reaches the conclusion that each theory is weak at best.

He summarizes: "You don’t have to be rich, but it helps. You don’t have to be growing rapidly, but at times rapid growth provides sufficient grounds to make the move. You don’t have to be desperately short of IPv4 addresses, but again it may help. You can do it by yourself, but it can help when your competitors do it as well."

Or, in other words, one of the world's foremost experts in IP addresses has no idea what drives and does not drive IPv6 adoption, is unable to find a good correlation anywhere that would help understand or predict adoption, and is alarmed to find that such adoption is slowing – and doesn't know why.

We have a theory drawn from another field that may help explain the growth – and slowdown – in IPv6 adoption: influencers and champions.

Human element

If you remove the technical requirement to move from IPv4 to IPv6 – because, the truth is, you can currently do whatever you want with IPv4 – you also remove the financial driver – which is what would typically drive an issue rapidly up the organizational chain. That leaves the human component.

We are willing to bet that at corporations with large IPv6 uptake there was either an individual or group that felt strongly about the issue and were in a position to persuade those at the top.

It's not hard to imagine why Google and Facebook have high adoption rates – because engineers have a strong voice and are listened to because the company was built by engineers and the companies are reliant on staying a step ahead on internet technology. LinkedIn is another good example.

But – as Huston notes – what are we to make of T-Mobile USA which has a massive 94 per cent adoption when Comcast has just 73 per cent; and what about BSkyB with its 93 per cent, where NTT in Japan has just 28 per cent?

"I suspect that this is a reflection of the difference between mobile ISPs and fixed infrastructure of mixed ISPs, and even the dual stack technology used by the mobile ISP," Huston posits. T-Mobile USA, for example, went all in on IPv6 and has added technology to be able to provide IPv4 services (a similar approach adopted by the big tech giants).

"It is likely that the lower numbers reflect an ISP that has integrated a number of different consumer products into a single autonomous system, and only some of the products have integrated IPv6 support as yet, or the numbers reflect a combination of customer equipment capability overlaid on the ISP’s network IPv6 capabilities," he argues.

Again though we see human persuasion at work here: someone persuaded T-Mobile USA that rather than go with IPv4 equipment, they should make the jump to IPv6 and then back port to IPv4.

T-Mobile USA is known for having a CEO who is focused on shaking up the mobile market and has gone out of his way to identify and promote small gaps in that market as a way of building up customers. In other words, the company is not only open-minded but is actively seeking an edge in the market.

Risk

Comcast on the other hand, while it continues in some respects to sit at the forefront of technology – such as its push on DOCSIS 3.1 – it is one of the big beasts and clearly doesn't see IPv6 as a risk to its market power or much of a help in expanding.

The same is likely true for most ISPs: they have their market and find more value in pushing non-technical marketing messages to get and retain customers. While there is some evidence that IPv6 can result in faster website load times, the issues and complexity around shifting to the new protocol are masking them.

Internet users continue to decide on their ISP based on three main factors: availability, price and speed/bandwidth. The existence of IPv6 is largely non-existent in the consumer's mind when it comes to making that decision. And it's difficult to see when it ever will be.

So, with IPv6 adoption costing money and chewing up resources with no clear, quantifiable benefit beyond it being the right thing to do, it shouldn't be much of a surprise that a big chunk of the internet isn't persuaded why they should shift.

If you take that assumption, a tail off in IPv6 adoption would make sense – those that have decided to shift to IPv6 have increasingly done so. Those that couldn't care less aren't going to do anything until they have no other choice; and the remainder will put it on the back burner until and unless it becomes important.

The bigger questions to ask at this point – nearly 20 years after it was first introduced as a draft standard – may be:

- What benefit does an IPv6 company actually derive from its more technologically advanced position? And

- Does it really matter if we live in a 25 percent IPv6 / 75 per cent IPv4 world?

It's hard to imagine a singular event causing everyone to suddenly rush to IPv6 so we are likely to see it becoming one of those issues where it relies on a new CTO and ageing existing technology to drive a revamp.

Maybe we should start viewing IPv6 as we do an operating system update. But an update that is incompatible with the last one. Companies like Microsoft and Apple have typically gone out of their way to make sure that the next operating system is largely compatible with the last.

And, of course, they have lots of other ways to drive adoption to the latest edition – withdrawing technical support, adding new bells and whistles, requiring greater processing power and so slowing down older versions.

None of that is true with internet protocols. Which means that IPv4 is the equivalent of submarines running Windows XP. So long as it still works, there is going to be significant resistance to moving. ®