This article is more than 1 year old

Just in time for summer boozing: Boffins smash world record for the most perfect ice cubes

It's Pimms O' Clock somewhere in the world right now

An international team of chemists has set the new record for crafting near-perfect cubic ice crystals. Sadly, the ice cubes are so small, they are invisible to the naked eye.

This is according to a study in The Journal of Physical Chemistry. It might sound trivial, but it is an extremely difficult task – one that involves condensing nitrogen and water vapor first, before blasting the tiny, frozen water drops out of a nozzle at supersonic speeds.

The water molecules in most forms of ice – in frozen lakes, snow or ice cubes – exist in a hexagonal structure. Trying to force the careful arrangement of hydrogen and oxygen atoms into a cubic shape is difficult, since it’s an unstable structure.

No scientist has ever managed to create a pristine sample of ice completely made from cubic ice crystals. The new study has managed to create ice that is nearly 80 per cent cubic and 20 per cent hexagonal, beating the previous record by about 10 per cent.

Barbara Wyslouzil, co-author of the paper and a graduate research associate at Ohio State University, said: “While 80 per cent might not sound ‘near perfect,’ most researchers no longer believe that 100 percent pure cubic ice is attainable in the lab or in nature.”

Wyslouzil told The Register: “[The researchers] also saw that the fraction of ice that was cubic in nature increased as ice froze from colder and colder water. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to cool water past a certain point. In our experiments, however, we can cool water further than others can by working with very small droplets. So we wanted to know: how pure can we make cubic ice?”

This rare form of ice is believed to form in the coldest clouds sitting at the highest altitudes on Earth. Scientists think cubic ice may be responsible for creating light halos that are sometimes visible around the Sun, as the sunlight is reflected from the clouds.

Cubic ice in clouds can scatter sunlight, creating concentric rings of light around the Sun (Photo credit: Pixabay)

By recreating this form of ice, the researchers believe it might enhance their understanding of the way clouds interact with sunlight – an important process that could improve climate change models.

To create the cubic form, the nitrogen and water vapor were drawn in with a supersonic nozzle. The gas inside expands and cools, forming tiny water drops measuring about 20 nanometers across – much smaller than any raindrop. The drops were then chilled at ‑48°C (‑55°F) and froze in about a millionth of second.

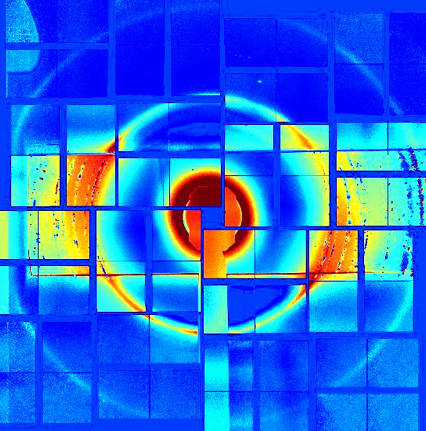

Researchers then used X‑ray diffraction – a method that involves shining a laser on a material and measuring the deflection of the X‑ray beams – to probe the atomic structure of the droplets.

Dude, you’re so square ... Concentric rings formed by X‑rays scattering off the ice droplets and reveal their internal structure (Photo credit: Ohio State University)

How water freezes on a molecular scale is still a mystery, said Claudiu Stan, co-author of the paper and research associate at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, California.

“When water freezes slowly, we can think of ice as being built from water molecules the way you build a brick wall: one brick on top of the other. But freezing in high-altitude clouds happens too fast for that to be the case – instead, freezing might be thought as starting from a disordered pile of bricks that hastily rearranges itself to form a brick wall, possibly containing defects or having an unusual arrangement.

“This kind of crystal-making process is so fast and complex that we need sophisticated equipment just to begin to see what is happening. Our research is motivated by the idea that in the future we can develop experiments that will let us see crystals as they form.” ®