This article is more than 1 year old

Colliders, containers, dark matter: The CERN atom smasher's careful cloud revolution

No downtime till 2018

CERN made headlines with the discovery by physicists in 2012 of the Higgs boson, paving the way to a breakthrough in our understanding of how fundamental particles interact.

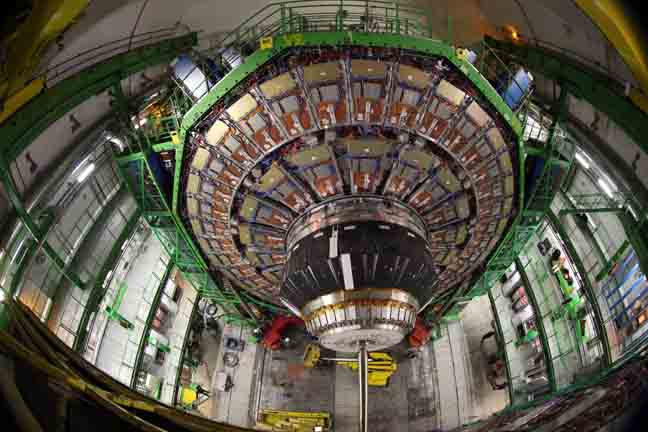

Central to this was the Large Hadron Collider – a 26km ring of interconnected magnets chilled to -271.3C straddling the Franco-Swiss border. The LHC is the world's largest and most powerful particle accelerator.

But 2012 was notable for another reason: an overhaul of the IT infrastructure that CERN's army of physicists using LHC and four other accelerators depend on to run their experiments and crunch their data.

In came OpenStack – then two years old – replacing a stack of in-house Perl scripts. Also new in was CentOS, Ceph, Hadoop, Kibana, Jenkins and Puppet.

OpenStack introduced elastic compute to CERN, a software-defined infrastructure giving scientists the resources they want in the time it takes to get a cup of coffee rather than raise a helpdesk ticket and then wait for the Linux servers to be reconfigured.

CERN is not defined by Higgs and its physicists are today probing areas including dark energy and dark matter. Something that's also evolved in that brand-new IT infrastructure is containers.

"One thing we've seen a lot of recently is container technologies," Tim Bell, CERN's head of computing told The Reg during an interview.

Yes, containers have been taken on across the entire industry but have found particular utility among the atom smashers of CERN.

Containers have become a way for scientists to run legacy code from old experiments with newer work – the CERN laboratory is 63 years old and the LHC was fired up in 2008. Applications are written mostly using C++ with some Fortran and Python. Despite this, there's a range of code that needs updating.

Bell told us: "The ability to encapsulate in the whole container the software and the operating system is very interesting. When we are running legacy code from previous experiments that need to be nicely isolated from where we have applications broken down into micro services that have different operating system requirements – we can meet that with a set of containers.

Insertion of the LHC beam pipe during a scheduled shutdown. Photo copyright CERN

"We are already seeing cases where one piece of code has been upgraded to the latest version but not another part – having this flex is a very interesting option."

So far, CERN has a small container environment – 1,000 nodes were spun up during a Kubernetes stress test that served seven million requests.

But from small beginnings come big things, and the experiment proves what the IT infrastructure is capable of delivering. "It means if someone comes to us with a large application, the fact we have done a significant scaling test means we are confident of meeting that need," Bell said.

No nasty surprises – or smooth evolution – is vital for an infrastructure as important as CERN's. Its OpenStack clouds run 24/7 – workloads are constant with experiments and results crunched on available compute.

Downtime, when it happens, takes place at phased intervals.

Operations on the LHC itself are planned in a series of what CERN calls "runs" of three to four years in length with a shutdown in between for upgrades to the accelerator and the experiments between runs. The current run, number two, is due to end in 2018 with the subsequent shutdown scheduled to finish in 2019.

As for the lifespan of CERN's servers, that's typically five years.

"There's always interest in tracking what happens in tech. We are a naturally technology oriented organisation – so people do experiment with Go and things like that," Bell explains. "However, there's also and understanding of the cost."

Bell's infrastructure team therefore performs careful due diligence on any new technology that its scientist-coders wish to run on OpenStack.

"If every time you adopt the latest language then after 10 years you have a wide variety of different things that a new person has to learn, so we are attentive of the fact we need to not only look at what's the latest thing but also the sustainability of the underlying environment."

New technologies are therefore subject to extensive pilot-phase testing. "Sometimes these things sounds really great when you read the blogs but it's only with real life that you can assess the application architecture," Bell said.

The embracing of open source at CERN extends beyond just the technology. It's a philosophy, too – a fact that helps Bell's team minimise adoption risk.

CERN works with open-source communities at an early stage of project development, feeding in ideas and helping make sure changes are threaded into its own infrastructure gradually – once code has been productised.

"One of the things we have been doing is work upstream of open-source communities like OpenStack, which means we can contribute improvements but – equally – look to the community, which we can also be helping out, for the long-term sustainability," Bell said.

Engagement also means CERN's engineers get to understand new technologies before they are finalised.

"A new person is actually mentored as part of their work with the community giving feedback on the code they've submitted, so we don't need to do everything ourselves," Bell said. "We can use some of the communities to keep things going and contribute to them."

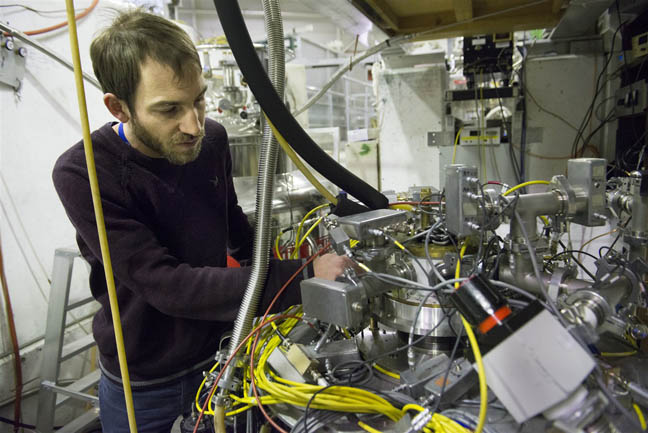

The Antihydrogen trap experiment to compare hydrogen atoms with their antimatter equivalents. Photo copyright CERN

When it comes to judging which open-source projects or software to bring onboard, CERN applies a number of rules: diversity – are you working on a project with one vendor or different vendors? – quality of documentation, and does that project follow open-source processes?

And even after that, CERN treads carefully as – even in open source – choices can mean commitment and an unofficial lock-in. Nowhere more so than in the fast-paced world of the developer, where if you're "right" technology adoption comes fast.

Take containers. Following a six-month pilot on 20 applications, CERN at the end of 2016 adopted OpenStack's Magnum to run Kubernetes, Mesos, Docker and Swarm, side-stepping the need to commit to one early on in the life of containers. Should a shakeup or consolidation hit containers, CERN shouldn't be left high and dry.

"We don't need to make a choice at this point which one is going to be the most popular – we can let users choose the one they like," Bell said. "The users were very interested in container techs and it also wasn't very clear what the best container orchestration engines would be.

"Magnum lets us use all the investment we'd got in OpenStack in Project Magnum quotas and in capacity planning and deliver a container orchestration as a service that allows the user to get the Kubernetes cluster in a click."

Retiring servers

It's not just CERN's software that's evolving – so, too, is the hardware powering it. One factor is the driving nature of CERN's 25 experiments and the volume of data they generate. That volume has nearly doubled in the last few years: an archive of 100PB in 2014 is now 187PB with an extra 49PB from the LHC alone in the last year.

Storage hardware has increased – 12,500 servers, 85,000 disk drives and 24,000 tapes today versus 11,000 servers, 75,000 disk drives with 45,000 tapes in 2014.

Applications and compute that had been running on four massive OpenStack clouds of 3,000 servers and 70,000 cores are today on 7,000 and 220,000 cores with 100,000 added to the compute fabric since last October.

CERN works closely with Intel to find out what's coming in chip giant's planned roadmaps to keep abreast of changes.

As Intel's hardware has changed CERN is now, for the first time, retiring its older servers.

Systems are coming in that deliver greater performance and power efficiency. The new systems are based on Intel E5 2650 processors with 40-48 cores, replacing Intel L5520 with 16-core configurations. CERN is conducting live migrations using OpenStack.

All this as CERN has begun optimising its programs – those experiments expressed in code on colliders like LHC – for parallel processing.

"With multiple simultaneous collisions... trying to work out whether a proton collided here or there is a complicated computing problem and that's where we are seeing an exponential computing growth – data comes in and computing goes up," Bell said.

"There's all kinds of work we need to do on algorithms and the programs – we won't necessarily be meeting all this computing need by putting in more cores. There's a very big effort going on with the experiments to optimise their programming on the environments we have.

"For example using the latest features of processors like vectorisation, getting more running in a parallel stream at any time – that requires a lot of work on the physics code that's been developed over the last 10-20 years, so with that some of the algorithms need to be reworked to be tuned to the latest generation of processors.

The control room at CERN. Photo copyright CERN

"The way the physicists work is they build different analysis algorithms within a framework but one of the challenges is if the code's been written by a large number of people so that it optimises a large program – that requires breaking that down and finding the core algorithm and optimising them."

CERN is restricted in its physical expansion, power and cooling – one reason for work virtualization. CERN runs 26,000 virtual machines, an increase of about 10,000 since 2015. CERN has also started to run workloads on public cloud – the Helix Nebula imitative has been run on 4,000 nodes in T-Systems' Open Telecom Cloud.

There have also been tests on AWS. The experiment there is as much business as technical – testing whether AWS can be purchased via CERN's standard procurement model.

Bell says CERN is interested in how far it can adopt standard public cloud resources through its standard procurement models. "That's one of the interesting questions: how to purchase bulk resources from hyper-scale providers," Bell said.

For Bell, yes, the future of CERN's technology evolution is about embracing the new but making it fit comfortably within that big-bang infrastructure upgrade of 2012.

"There will certainly be major technology changes – we are looking around at GPU and multi-core technologies and through collaboration with the industry we investigate those," Bell said. "We saw a major transformation in 2012 in how we did IT and we hope that model would continue for a significant time.

"I'd certainly expect you'd continue to see disruptive technologies like containers to continue to appear, but what I'd hope is you'd keep the same framework so they aren't so disturbed by their appearance." ®