This article is more than 1 year old

This is how the EU's supreme court is stripping EU citizens of copyright protections

Pirates, rejoice! The rest of us... er...

Special Report An upcoming EU court decision could strip half a billion EU citizens of their copyright protection, and all because of an accidental translation error.

In practice, it means that a link to your stolen family photos (which would never happen because the cloud is so secure, right?) would be free to circulate and there’s nothing an EU citizen could do to have the link taken down.

The story has a surreal quality, as international experts can't understand how the EU's highest court is talking itself out of the international copyright system.

Quite by itself (and in a short space of time) the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg (CJEU) has developed its own legal theory for copyright, which it has subsequently expanded in successive decisions. The concept is unique to the CJEU and isn’t used in any other jurisdiction in the world, and isn’t part of the Berne Convention which obliges the EU to provide copyright protection to its citizens.

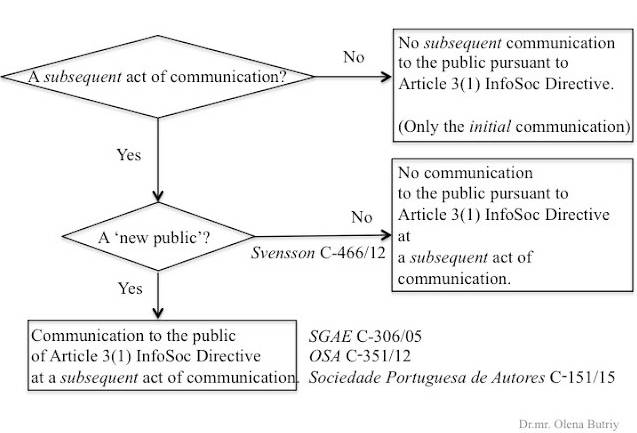

The concept is “a new public”, and the EU court uses this to begin to weigh the claims of whether a usage of some material is legitimate or not. In the rest of the world, the law starts to judge matters on whether something is “a new communication to the public”.

It’s the same words, but in a different order – and of course, a "new public" means something completely different to a "new communication". Instead of having to establish whether there has been a “communication”, Justices must now agonise of whether the communication has reached “a new public”.

Legal scholars and rights holders are alarmed, and not only because the detour promises to put blatantly scofflaw operations such as the Pirate Bay beyond the reach of copyright countermeasures in the EU. Legal experts point out that because the “New Public” concept is new, and unique to the EU, it’s being redefined in often completely contradictory ways. Like Humpty Dumpty in Alice in Wonderland, “new public” is whatever the CJEU can choose it to mean on a particular day.

Ironically, the character of Humpty was Lewis Carroll’s satire, in Alice in Wonderland sequel Through the Looking-Glass, of Continental philosophy.

What’s the New Public Theory, and where did it get here?

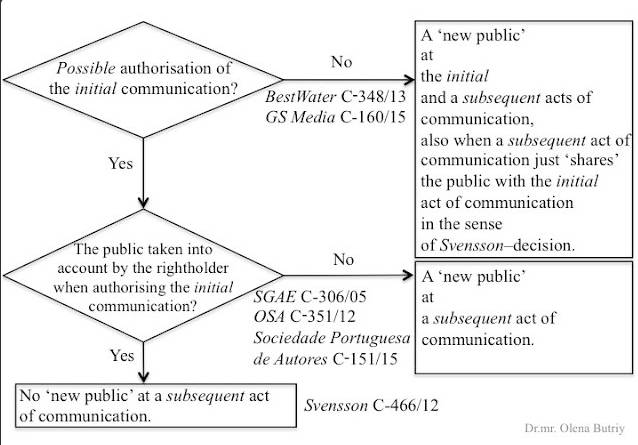

The CJEU has evolved the New Public Theory by itself through successive decisions. Any court, anywhere in Europe, at any level, can refer a matter up to the CJEU for “clarification”, and there's no consistency in their verdicts: different justices in Luxembourg all have different ideas on what a New Public could be.

But it’s an opinion by the controversial EU Attorney General, himself a former CJEU justice, the Belgian Melchior Wathelet, in a case currently before the court, that has ignited the latest concerns.

In this case, Wathelet, speaking about the GS Media v Sanoma Media case has recommended that the EU Court decree that no hyperlink could ever be the basis of a copyright infringement case.

The CJEU is not obliged to follow its AG’s opinion – but if it does, then the Pirate utopia that John Perry Barlow advocated in his Declaration of Independence in Cyberspace in 1995 becomes a reality for 500 million EU citizens. It’s beyond anything the EU's only Pirate Party MEP, Julia Reda, could have dreamed possible.

There’s one slight wrinkle, however. A decision to put hyperlinks beyond the reach of copyright would place the European Union in breach of its Berne Convention obligations. And although EU citizens could do nothing about it (except hope for a subsequent, contradictory ruling), much of the material that would lose its copyright protection would belong to non-EU citizens. WIPO sanctions are available to any sovereign state against another if the latter is deemed to be breaching its obligations; WIPO administers Berne.

“What is happening now is they are running away with the concept, and the result is totally ridiculous,” Dirk Visser, Professor of Intellectual Property Law at the University of Leiden (who has litigated for and against copyright holders), explained.

Visser says the theory originated in a narrow technical context, of whether people watching TV cable transmissions in hotel rooms were a “new public”. It then got an airing in a case about the public watching TV in bars, but generally lay dormant for years. But after the formation of the CJEU – which was given supreme legal authority over the EU's 28 member states, after the agreement of the Lisbon Treaty, picked it up and ran with it. The CJEU’s 2014 Svensson decision saw the Theory take centre stage.

“In Svenssen, there is an ‘original public’ reached by the uploader. Therefore hyperlinking did not reach at new public, so there was no communication to the public. The implied permission was that so that everybody could actually access it.”

“That was strange but we could live with it. Now the initial public is still illegal, but nothing that happened after could be a communication,” Visser told us.

Another EU litigator added: "Any discussion that Sanoma never intended to make its photos available is absurd.”.

Hyperlinks aren’t a communication. Except when they are

Few infringement cases would seem to be as clear cut as in GS Media vs Sanoma, the subject of Wathelet’s potentially incendiary written opinion. The case concerns the actions of a Dutch online lads' mag called Geenstijl, which was tipped off to the existence of a Playboy shoot of pinup photos before Playboy had itself published them. The files surfaced on a cyberlocker called File Factory. Geenstijl gleefully provided the link, with the anchor text “HIERRR”.

The Dutch Supreme Court drew on the CJEU’s New Public-based ruling in an earlier case, Svenssen, to cut the lads' mag some slack. Court’s typically have to balance the fundamental right of speech in such judgements, but Wathelet’s opinion is unusual in that it removes the property right at all, thanks to the New Public logic.

If something has already been made public then they can not be suppressed, Wathelet reasons, because a hyperlink “does not constitute a ‘communication to the public’.” Say what? Welcome to justice, EU-style. The twisty logic removes, says Professor Dirk Visser, the ability to pursue a broad class of remedies such as takedowns. "Only by imputing a form of liability or at least injunctive relief on a provider of a hosting service which imposes a duty on him to prevent the re-uploading of the same or any other clearly infringing material will render such an approach effective."

And apart from "diehard anti-copyright folks", he says, it's hard to see who could be happy with such a verdict.

The argument that the EU’s “New Public” theory makes the EU an outlaw state was advanced by someone who should know. This is scholar Dr Mihály J. Ficsor, who (literally) wrote the book on copyright for the World Intellectual Property Organisation.

“The ‘New Public’ theory – as outlined in the court’s SGAE ruling – is in conflict with the international treaties and the EU directives,” Ficsor wrote in 2014.

In Ficsor’s account, the CJEU used the wrong copy of his textbook.

The theory was adopted because the CJEU – recognizing WIPO publications as a reliable source to clarify the concept of communication to the public – relied exclusively on an old 1978 WIPO Guide to the Berne Convention (and misinterpreted it) rather than (i) on the text of the relevant norms and of their “preparatory work”; (ii) on the thorough analysis made in authoritative copyright treatises; (iii) on the interpretation adopted by a series of competent WIPO committees of governmental experts; and (iv) on the new 2003 WIPO Guide reflecting that interpretation (refuting the “new public” theory).

We invited Dr Ficsor to elaborate but he had not responded to requests by press time.

Clear? Understanding the ECJ's New Public theory already requires significant mental gymnastics

In January this year something very unusual happened. A serving CJEU judge descended from Mount Olympus to talk to earthbound mortals – and to try and refute the view that it had all been a terrible accident.

In an account published on an activist blog (caveat lector), we learn: “Judge Jiří Malenovský of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) bravely faced a public of copyright scholars, many of whom had extensively raised concerns about decisions of the court in their academic outputs.”

English isn't the blogger’s first language, but from the account we find a distressed Judge Malenovský denying that the CJEU had pulled an entirely new legal theory out of its fundament. Malenovsky stressed that the property right and the right to expression were equal, but had to be balanced. He also denied the CJEU was in breach of international conventions. Those conventions are already incorporated in EU law, he said, so every judgement must be implicitly compatible with a convention. However, the property right has been extinguished in Wathelet's Sanoma recommendation, as a hyperlink acquires a kind of sacred status.

The decision affects every European, but naturally trade groups for audio-visual industries are most concerned. In reality, the removal of copyright protection means an owner can still defend their property using tort law, but that’s much more difficult and expensive to defend.

"I hope full court will realise it’s running with scissors,” one told us. ®

Bootnotes

The "constitutional incoherence" was highlighted by Marina Wheeler QC here.

Melchior Wathelet was criticised for his role in the Dutroux affair. As Belgium's Home Secretary, Wathelet approved the early release of serial killer and paedophile Marc Dutroux in 1992 after serving only a small portion of his sentence. Dutroux went on to abduct and kill again before receiving a life sentence in 2004. Wathelet served as a CJEU judge from 1995 to 2003.