This article is more than 1 year old

Astroboffin discovers exoplanet by accident ... in 1917

No space telescopes required, archive discovery reveals

A reexamination of astronomical records has shown that an astronomer unknowingly snapped an exoplanet during the First World War – well before such bodies were confirmed in the 1990s.

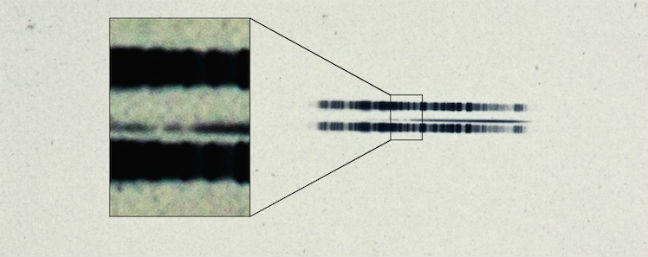

In 1917 Dutch-American astronomer Adriaan van Maanen, working at the Mount Wilson Observatory (then part of Carnegie Observatories), took a series of spectra images of different stars. The images were recorded by the then-Observatory director Walter Adams on glass photographic plates that showed the composition of the stars by the spectra of light emitted.

The astronomer discovered what was then the closest white dwarf star to Earth, later named Van Maanen 2, 13.9 light years away. As well as the helium and hydrogen we now know white dwarfs are largely composed of, the spectra recording showed large amounts of calcium, magnesium, and iron.

What wasn't recognized at the time was that such spectra readings are indicative of an exoplanet – a world orbiting a star. Scientists have since discovered that stars with this kind of chemical signature – so called "polluted white dwarfs" – show stars that are encircled with rocky debris and at least one large exoplanet.

The plate was filed and forgotten by Carnegie Observatories, but last year Dr Jay Farihi of University College London contacted the organization wanting to take a look at it. He discovered the evidence that Van Maanen 2 was indeed a polluted white dwarf.

The forgotten evidence

"The unexpected realization that this 1917 plate from our archive contains the earliest recorded evidence of a polluted white dwarf system is just incredible," said Observatories' Director, John Mulchaey.

"We have a ton of history sitting in our basement and who knows what other finds we might unearth in the future?"

The exoplanet assumed to be in orbit around Van Maanen 2 hasn't yet been spotted, but astronomers are going to use the discovery to check and Dr Farihi said that it was almost certain there is a planet in orbit.

"The mechanism that creates the rings of planetary debris, and the deposition onto the stellar atmosphere, requires the gravitational influence of full-fledged planets," he explained. "The process couldn't occur unless there were planets there." ®