This article is more than 1 year old

Cosmic blast mystery solved in neutron star's intense death throes

'As if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced'

A pair of European astrophysicists believe they've solved the mystery of exceedingly bright, never-repeated flashes of radio waves that come to us from the distant past.

The source of those brief, intense flashes can be defined in two ways, depending upon whether you'd prefer to look at the event as a death or a birth.

"We suggest that a fast radio burst represents the final signal of a supramassive rotating neutron star that collapses to a black hole due to magnetic braking," write Heino Falcke of Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and Luciano Rezzolla of the Albert Einstein Institute in Potsdam, Germany in their paper (preprint, PDF) "Fast radio bursts: the last sign of supramassive neutron stars" published in this week's edition of Science.

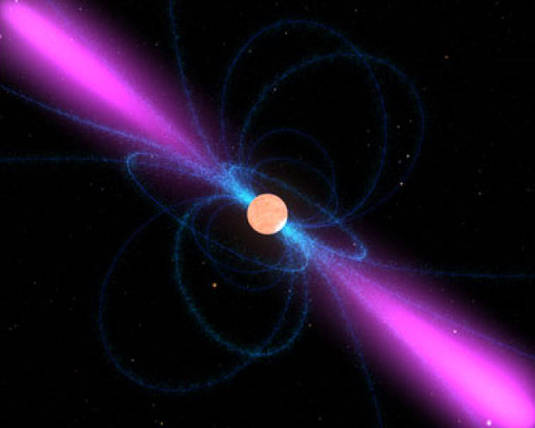

Neutron stars are ludicrously dense objects. According to the press release outlining Falcke and Rezzolla's findings, "They are the size of a small city but have up to two times the mass of our Sun."

As you might assume, something that massive has an upper limit on its mass, otherwise it would collapse in upon itself and become a black hole – and you'd be right. There are, however, neutron stars that are larger than the critical mass of about two solar masses, but that manage to keep from falling in on themselves due to their high rotational velocity.

Cleaning up the neighborhood in preparation from metamorphosis from neutron star to black hole

If an overweight neutron star is spinning fast enough, the centrifugal forces that are generated by that speedy rotation can counterbalance the forces of gravity, and keep the star from falling in on itself for millions of years – but not forever.

The reason for their inevitable doom is that neutron stars also have extremely powerful magnetic fields that radiate outward from them. "Over time," Falcke and Rezzolla write, "magnetic braking would clear out the immediate environment of the star and slow it down." And when it slows down sufficiently, the centrifugal forces diminish to an extent that gravity will achieve its inevitable victory.

Normally when a star collapses into a black hole, there is also a burst of optical and gamma-ray radiation. Not so in this scenario, seeing as that the rotating neutron star's magnetic field has already cleaned out the neighborhood, and that the event horizon of the black hole quickly engulfs the surface of the neutron star.

"All the neutron star has left is its magnetic field, but black holes cannot sustain magnetic fields, so the collapsing star has to get rid of them," explains Falcke. "When the black hole forms, the magnetic fields will be cut off from the star and snap like rubber bands," and that snap is what produces the immense, one-time radio flash that has been observed.

"All other signals you normally would expect – gamma rays, x-rays – simply disappear behind the event horizon of the black hole," says Flacke.

Falcke and Rezzolla have dubbed these objects blitzars – "blitz" being German for "flash" or "lightning". "A blitzar," Rezzola writes, "is at the same time the farewell signal of a dying neutron star and the first message from a newly born black hole." ®